In the first of a series of articles, Peter-James Gregory looks at the evolution of internal combustion engines and electric vehicles, leading up to a discussion about the role both can play in the future of transportation.

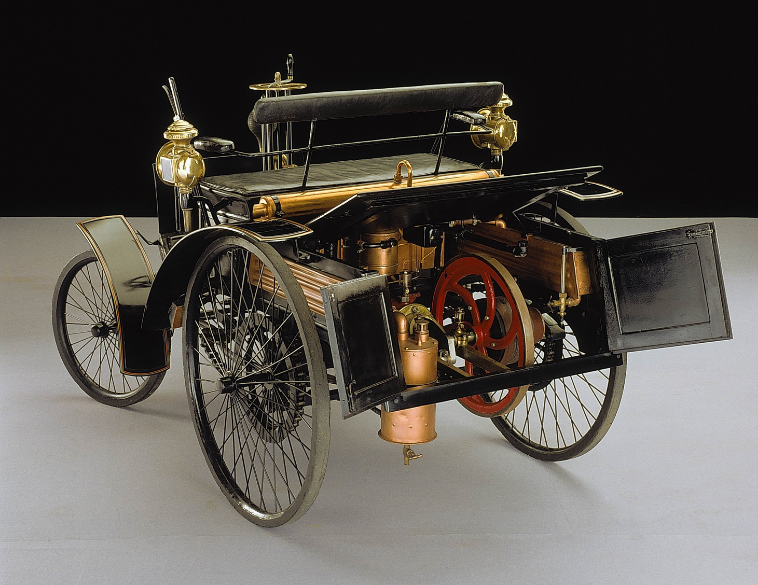

The Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) has been the main power unit for automobiles since 1886. Back then, Carl Benz obtained a patent for his “vehicle powered by a gas engine”, using a 0.75 HP single-cylinder four-stroke gasoline engine. This patent is seen as the birth certificate of the automobile.

However, this was not the first ICE developed by Benz. He previously developed a stationary gasoline two-stroke ICE that ran for the first time on New Year’s Eve in 1879. The commercial success of this stationary engine allowed Benz to devote time and resources to the development of a lightweight car powered by a gasoline engine. Note one of his criteria was lightweight.

An important role

While the focus here is automobiles, stationary engines have played an important part in industrial development. A stationary engine remains in a fixed position and drives generators or other machinery in a building, or other locations such as a construction site or mine. Stationary ICE units drive back up power generators at hospitals and at many other facilities critical for our life and liberty.

Like ICEs, electric vehicles also have a long history. Scotland’s Robert Anderson developed a motorized carriage in the 1830s using an electric power unit fed by batteries. However, as the batteries of the day were not rechargeable, this early EV was viewed as a magical amusement and not reliable transportation.

Rechargeable batteries became available in 1859 making the idea of EVs more viable. In 1890, a Scot living in Des Moines, Iowa, William Morrison, applied for a patent on his electric carriage. This early EV had 24 battery cells that needed recharging every 50 miles. It was a sensation at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and sparked the imagination of other inventors.

By the early 1900s, many manufacturers offered EVs. Studebaker, a storied automotive company (with Canada playing a prominent role in its later years), was building wagons and carriages in the 1800s and entered the 1900s as a manufacturer of EVs.

Better alternative

Detroit Electric offered an EV in 1923 with a top speed of 25 mph and a range of 80 miles. By then, however, ICE vehicles were more affordable, lighter, had better range and could be refueled faster. While service stations were not everywhere in those days, you could carry a jerrycan of gasoline and refuel at the side of the road in a few minutes.

Early EVs experienced the same challenges as current EVs—such as price, range and weight. By the 1930s most EV manufacturers converted to ICE or went out of business.

Here begins the journey to connect the dots and feed the practical mind. I hope this journey will illuminate a wider view of the power options for motor vehicles and encourage you to consider the practicality of each option when faced with the realities of daily life and daily business operations.

Each column will be a step on this journey. They will not be heavy on statistics but all the data and statistics to support the columns are easily available on the Internet and from various publications. I challenge you to do a little research…you may be surprised by what you find.

Read the second part here.