Traditional vehicle materials are evolving alongside new substrates.

As Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards are forcing automakers to build lighter vehicles, there’s been a significant growth in the use of aluminum, plastics and composites.

Despite this however, the steel industry—still the supplier of the bulk of fabricating material used in vehicle construction isn’t resting on its laurels.

Today, Generation 3 advanced high strength steels are designed to not only offer increased strength, reduced weight and crash resistance but also greater formability. When it comes to creating new steels, the process can almost be compared to making bread. The material is rolled and different ingredients added to achieve the desired results.

Creating steel is a compromise of different properties that enable the steel to be formed without cracking, maintaining integrity in the face of damage and ensuring long-term durability. It still must be affordable and light enough to compete with other materials, given that OEMs are under enormous pressures to increase fuel efficiency.

Up until the 1980s most cars and trucks were made from mild steels, also called carbon or plain carbon steels, which have very little alloying element. These steels have a maximum tensile strength of 280 MPa (40,000 PSI) and are very easy to form. Vehicle size was considered a safety aspect back then and relatively cheap fuel meant that vehicle weight was generally of little importance.

As automotive technology evolved, and fuel economy and safety became an increasingly important factor in vehicle design, HSS steels were introduced. The main strengthening mechanism in conventional high strength steel is solid-solution hardening. In the bake-hardenable (BH) steels, the chemistry and processing are designed to take carbon out of the solution during the paint baking cycle. In this way, the steel is made softer and more formable for the press shop, but it gains more strength after being put in service.

High-strength, low-alloy (HSLA) steels, introduced in the 1990s, are carbon-manganese (CMn) steels strengthened with the addition of a microalloying amount of titanium, vanadium, or niobium. These steels, with a tensile strength up to 800 MPa (115,000 PSI), still can be press formed.

The most recent evolution is advanced or ultra-high strength steels (AHSS) developed for the auto industry falling into three generations.

The newest of these, third generation AHSS, has been developed to optimize formability, durability and strength and can reach tensile strength as high as even 2,000 MPa.

Third generation AHSS is not one type of steel but includes a range of materials aimed to meet varying demands. These steels can be formed to more complex geometries, providing easier welding and lower cost by improving strength to weight ratios, making them a suitable substitute for aluminum in some areas. As the science evolves, more and more steels are being created for specific purposes.

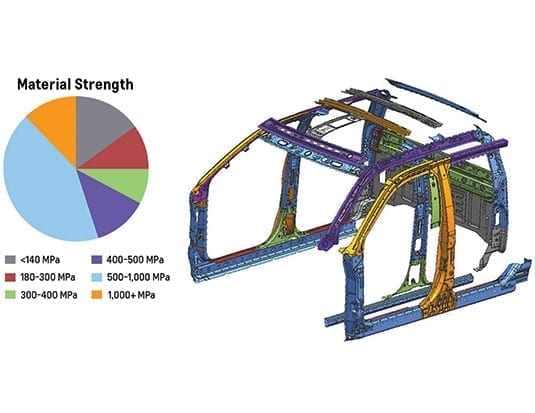

Third generation AHSS is being increasingly used for structural areas on new vehicle architectures such as firewalls and B-pillars where increased strength in combination with rigid design allows for thickness reduction and weight saving.

For collision repair shops, while it seems that aluminum and other substrates are increasingly being used, steel still has a very important role to play. And ensuring the correct procedures in repairing the newest generation AHSS materials are followed is essential.